Since posting about Private Melvin J. Schenck several weeks ago on Veteran’s day, I became curious about whether some Internet searching might produce additional information regarding the circumstances under which Melvin was captured and held as a prisoner of war during the later part of World War II.

After just a few minutes searching, I was surprised to locate three reports related to the 394th Infantry Regiment Medical Detachment, 99th Infantry Division, which was the Detachment to which Melvin was assigned. The reports, prepared by Major Stephen M. Gillespie, cover the time period during which Melvin was captured and which I soon learned were also the opening days of the final German offensive of World War II – known to most of us as the “Battle of the Bulge”.1

Using one of the reports prepared by Major Gillespie, I prepared a brief summary of the events which occurred in those first few days of the Battle of the Bulge, specifically as they relate to what most likely happened to Melvin and his Medical Detachment.

The summary is as follows:

German troops began “laying down heavy artillery barrages in Hunningen, Belgium, site of the Regimental Command Post, and Regimental Aid Station” at 5:00 a.m. on December 16, 1944.2

The shelling continued throughout the day and into the next until the Regimental Aid Station received word at 2:00 p.m. on the 17th to withdraw to Murringen – a distance of a little over one mile to the north. The relocation was completed by 7:00 p.m. that night. Medical personnel set up aid stations in basements of shell torn houses in Murringen, which provided cover from “inclement weather” so that the wounded could be treated.3

Shortly after setting up in Murringen, the town was shelled by the enemy and the barrage lasted the remainder of the night, forcing the aid station to be moved into the cellar of the house where five litter patients were placed and treated along with a large number of walking wounded. Lighting was poor and though candles and flashlights were used the patients were given the best of care.4

By the next day, after two sleepless nights and no food, and realizing they were cut off and completely surrounded by the enemy, the Medics made the decision to empty their pockets of all personal items. As stated by Gillespie, “Time passed slowly and the shelling of the town seemed to increase with each minute . . . ” 5

At 1:45 a.m., word was received that the Regiment was to make a withdrawal at 2:30 a.m. No ambulances were available to transport the wounded so it was decided to unload a 2 1/2-ton truck of Medical Supplies and Equipment to use for transportation of the wounded. Four litter wounded and three Medics were placed on the truck; the walking wounded and remainder of the Station personnel boarded the Regimental CP truck. The officers traveled by jeep.6

The convoy left Murringen at 2:35 a.m. and headed two miles north for Krinkelt. Almost immediately, an order came to abandon the vehicles due to enemy action at the head of the column.7

Troops then began to move on foot . . . but were halted alongside the roads when small arms fire was heard and flares lit up the terrain. A patrol of infantrymen went ahead and upon returning informed the Commanding Officer that the city was now in American hands.8

Once again they boarded the vehicles and the convoy made its way to Krinkelt and continued on to Wirtzfeld, another mile to the west. One hour after arriving in Wirtzfeld, the battalion aid stations and Regimental group accompanied their respective units on a march to Camp Elsenborn, a former Belgian military base.9

Upon arrival in Elsenborn, a “check-up” on personnel was made and it was found that one-third of the Detachment was missing.10 In addition, the Regimental CP truck carrying the walking wounded and aid station personnel had not yet arrived. Sgt. Clarence F. Flynn, Acting First Sergeant and a passenger on the CP truck, later arrived and reported that the truck had been ambushed by the enemy a half-mile outside of Murringen. Five passengers were wounded.11

Sgt. Flynn was instructed to treat a wounded officer by the Germans and while he was rendering aid the other members of his party were marched away. The enemy left a company at the truck to guard it as well as Sgt. Flynn and his patient.12

Sgt. Flynn and another captured soldier later escaped from the Germans. The following day, the 19th, Sgt. Irvin S. Rosen, who was also captured on the CP truck by the Germans, made his escape when the enemy instructed him to enter the City of Krinkelt and plead with the Americans to surrender. Instead, he gave information as to the location of the Germans.13

Early on the afternoon of the 18th, the Battalion Aid Stations and Company aid men left Camp Elsenborn for the front. Aid Stations were set up in Elsenborn and advance stations put into operation at the front.14

The ensuing battle at this location is known as the Battle of Elsenborn Ridge – “the only sector of the American front lines during the Battle of the Bulge where the Germans failed to advance.” 15

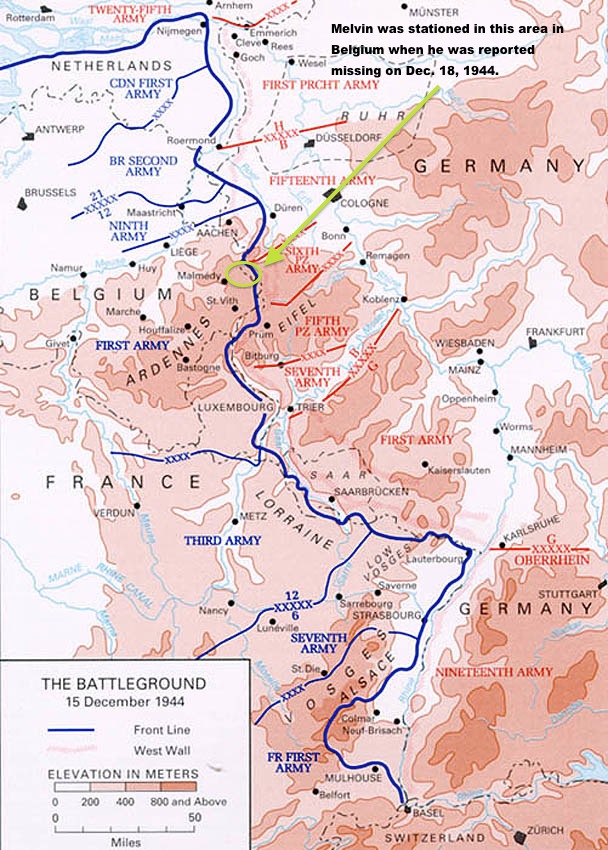

The map below details the area discussed in this post.

In a future post, I will share what I’ve learned about the POW camp where Melvin was held and later died.

SOURCES

- See Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Battle of the Bulge,” rev. 2 Dec. 2015. ↩

- “Medical Detachment, 394th Infantry, 99th Infantry Division, 1 January 1945.” U.S. Army Medical Department Office of Medical History (http://history.amedd.army.mil : accessed 01 Dec. 2015). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- It seems likely that Melvin was part of this missing group, probably captured somewhere between Murringen and his group’s arrival at Elsenborn. ↩

- See “Medical Detachment, 394th Infantry, 99th Infantry Division, 1 January 1945.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Battle of Elsenborn Ridge,” rev. 17 Nov 2015. ↩